Rising Utilitarianism in Decision Making: Cause Marketing

This article originally appeared on CoreyPadveen.com.

More so than ever before, we are seeing businesses adopt causes as core components of both their business and marketing strategies.

Cause marketing is nothing new. Examples of truly integrated cause marketing go as far back as the 70s. What we’re seeing today, however, is a shift in the way causes are being integrated into the missions of businesses; this holds particularly true for businesses that try to appeal to millennials (and often succeed). Let’s start with first taking a look at what exactly cause marketing is and how it falls into the discussion of utilitarianism in decision making.

(Modern) Cause Marketing: What is it?

Almost immediately, I’m sure, most people jump to the idea of defining cause marketing as the concept of brands teaming up with a particular charity or non-profit for a given campaign where “a portion of the proceeds…” – you know the rest. While that is one definition of cause marketing, I would like to look at a somewhat more modern approach, which has seen a rise in recent years.

The definition I would like to consider for the examination of how cause marketing highlights utilitarianism in the decision-making process is one where brands do not simply partner with a cause for a particular campaign, but rather adopt the cause themselves, creating an inextricable link between the brand and the cause itself. This is to say that in lieu of a third party partnership, the cause is the brand and the brand the cause. Don’t get me wrong – there is nothing better or worse than those third-party partnerships. For the case of this argument, however, I would simply like to look at the brands that have made their for-profit businesses cause-centric, and how this strategy has paid off.

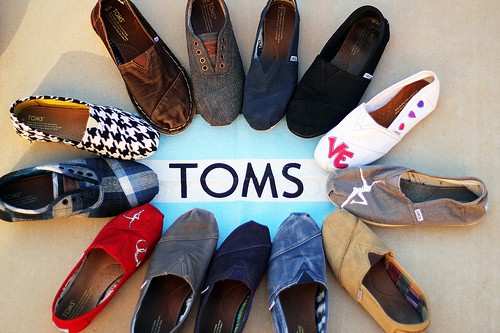

One of the most notable examples, and one that I make reference to in my book, Marketing to Millennials for Dummies, is TOMS shoes.

TOMS shoes is by no means the first company to align with a cause. They did, however, approach their alignment is a unique way. Instead of donations in cash from each sale, TOMS offers up their ‘one for one’ structure, where they donate a pair of shoes to those in need for every pair sold. The costs of production and logistics are factored into the cost of each pair, and they make that very clear in their mission statement. As opposed to consumers – a huge portion of whom are millennials – shying away from an overtly inflated price tag, they happily pay for the price of two when they are getting one. (Yes, I know that simplifies the whole transaction a little bit, but you understand my point, I hope.) It is in this willingness to buy TOMS over simple, less expensive alternatives that we see utilitarianism poking through.

An Example of Utilitarianism and Economic Utility

By now (if you’ve been following this series of articles) you already have a pretty good grasp on what exactly constitutes utilitarianism, so in the case of cause marketing, it should be pretty obvious.

Utilitarianism has everything to do with making the decision that benefits society as a whole. In this case, we’re talking about the consumer’s decision to buy a product from one manufacturer over another based on its alignment with a particular cause. As much as it may seem contrary to what the majority of societal assumptions suggest, in the case of millennials, this might mean spending more for a product based on the company’s alignment with a given cause. Most marketers’ definitions of millennials focuses intently on their unwillingness to spend. When looking at the actual data, however, we see that certain instances, like those involving cause marketing, lead to a higher transactional spend and lifetime value.

A point that I have regularly reiterated is that millennials, and modern consumers in general, weigh the overall economic utility of their purchases when making a purchasing decision. When it comes to brands that have involved themselves in cause marketing, there is a greater economic utility for the consumer, since the purchase, however much more expensive provides them with the knowledge that the transaction wasn’t simply fleeting, but rather ongoing. They are getting more out of the transaction based on the knowledge that it also involved a cause. In the case of other causes, such as the checkout dollar donation, the transaction feels separate. As a result, it doesn’t have the same added value to modern consumers as the integrated cause marketing, as is the case with TOMS. As a result, this new form of cause marketing resonates significantly with modern marketers, and showcases a clear example of utilitarianism and economic utility melding together, once again, to highlight the new means of consumer decision-making.