The Unintended Rise of Utilitarianism in Decision Making (Part 1)

This article originally appeared on CoreyPadveen.com.

Whether or not we meant for it to happen, utilitarianism has become a driving factor in the decision-making process.

Millennials are often regarded as being self-absorbed, lazy and entitled. Vanity and the pursuit of perceived perfection have led to the presumption that millennials and, more broadly, the consumer market in general (for the most part) are entirely self-centered. It is easy to see why that way of thinking has become commonplace. All of the superficial elements are there to support the argument. What might surprise you – as it did me – is to discover that consumers are not as self-obsessed as we might think and that when we take into account modern technology trends, consumption habits and general social behavior, we can see that, in fact, quite the opposite is true.

I’m talking about an individual pursuit of utility maximization rooted in the moral base that defines utilitarianism. To explain how I came to this conclusion, it’s going to take a few articles. Over the next few weeks – or months, or years, who knows how much I’ll end up writing – I’ll be gathering my thoughts and covering how these two concepts – that of economic utility maximization and utilitarianism – relate to the various habits of modern consumers. In this first segment, I’ll cover the two umbrella topics that provide the basis for my argument. Let’s first take a look at economic utility.

Economic Utility

What exactly is economic utility? Well, the definition, pulled below from Investopedia, is fairly straightforward:

The value, or usefulness, that a purchaser receives in return for exchanging his money for a company’s goods or services.

While this definition is simple enough, the key point of focus needs to be on the concept of value, rather than the tangible transactional details. Exchanging money can be substituted for virtually any type of exchange. The value derived from a transaction is an intangible metric, and in traditional microeconomics, its calculation relies heavily on presumptions made by the economist. Modern behavioral economics, on the other hand, looks at value for what it is: an individualistic motivator that leads largely irrational consumers to improve their economic well-being by choosing an option that leads to the greatest returns. Those returns come in many forms, but the key point to remember is those transactional decisions, on an individual level, are self-serving and aim to derive the longest-lasting dividends.

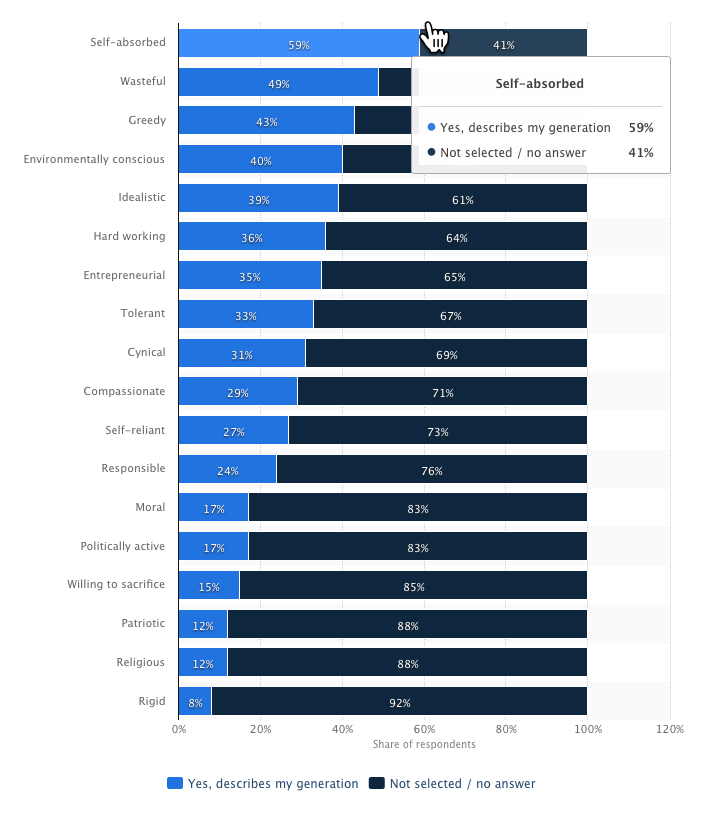

It is as a result of this concept of economic utility maximization that we get the overwhelming societal opinion that millennials act purely out of self-interest. A 2015 survey by Pew even found that millennials see themselves as self-absorbed a greedy, which you can see in the chart below:

So, on an individual level, based on some of the core constructs of behavioral economics, we are all trying to get the most out of every transaction. The motivation behind our decisions is, rather understandably, to make our lives better in whatever measurement criteria we use to define that metric. Individual economic utility maximization, when trying to understand it from a philosophical standpoint, would fall pretty closely in line with egoism. If that’s true, then this consumer trait and the subsequent actions taken by consumers have the potential to conflict pretty directly with the fundamentals of utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism

Before getting into the specifics of the theory of utilitarianism, let’s take a quick step back and talk about consequentialist ethics. In philosophy, a theory is considered consequentialist when the morality of a decision is determined based purely on the outcome of said action. So, if the consequence of an act is considered good, then the action is right. If the results of an act are wrong, then it is considered bad. Pretty straightforward stuff. Both utilitarianism and egoism are considered consequentialist in nature. The difference, however, is that with egoism, as you saw above, when it comes to economic utility, the entirety of the consequence relies on the outcome for the self. That does not necessarily hold true when it comes to utilitarianism.

The utility in the case of utilitarianism is slightly different than that in economics. In the case of utilitarianism, the outcome of an action needs to provide the greatest good for the greatest number of people. This might mean that a morally right action has a lesser benefit on the self, but the welfare of society as a whole is improved. While there is clearly overlap in these two cases, we can almost certainly think of a nearly endless list of examples where the decisions made under the assumptions of egoism will not necessarily line up with those made under utilitarian principles. Take, for example, the case of Edmond Dantès in Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. Under the guidelines of utilitarianism, Dantès would have shared the treasure he discovered with society so as to improve the well-being of every member of society. His choice, clearly rooted in the morality of egoism, was to keep the treasure in order to improve his own welfare and achieve his goals. There are plenty of cases where this outcome might arise, and this particular example is relevant because it has to do with money – or, in the case of the transactional examples noted in the previous section, it has to do with improving one’s own economic utility.

So, thinking about examples in this way, you can probably see how economic utility, a primary driver of consumers’ decisions (particularly millennial consumer decisions on an individual level) might conflict with utilitarianism. And yet, when we take a step away from millennials’ individual actions and look at the trends, emerging economies and social standards set by the demographic as a whole, then we start to see millennials’ operating under the guise of utilitarian ethics.

Over the course of this article series, I will be looking closely at several examples that showcase this reality, juxtaposed against the perceptions we have about millennials on an individual consumer basis and, hopefully, convince you that the theory is true. Hope you enjoy it!